After thawing out from our first night in the guest house, Bob and I set about accomplishing priority one: getting our return tickets. Which meant going back to the train ticket office.

The Chengdu train station was like a caricature of the Beijing train station. Beijing was crowded? Chengdu was more crowded. Beijing was loud? Chengdu was louder. The posters warning of the dangers of fireworks were even more graphic and disturbing. And I thought the people in Beijing were pushy.

It was as though we were trying to buy tickets on the roof of the American Embassy before the fall of Saigon. It was every man for himself, pushing and shoving, flying elbows everywhere. Somewhere in the middle of it were two Americans whose sense of fair play was offended, wondering why people couldn't just wait their turns.

Fortunately, we were seasoned travelers now, and fortified by our success in Beijing. We got in line and we were ready to give as good as we got. There were some pushy grandmas who discovered the taste of my elbow on that day, I can tell you.

We coped as best we could with all the pushing and jostling, but eventually it became too much. A guy barged into the line ahead of us, and that was the last straw. It was time to play the foreigner-in-China card. The toddler-in-the-grocery-store card:

"Oh, so you think you can treat me unfairly without any consequences, do you? Well, think again."

Another variant is the crazy-guy-on-the-bus card. If people don't know what to do with you, they disengage and leave you alone.

Last Straw hadn't even bothered to pretend he wasn't doing it. So we raised our voices. In Chinese.

"Don't cut in line!" I said to this goof. (A useful phrase I'd picked up from our experience in Beijing.) He ignored me.

Bob got right close to him from behind and said something like, "most Chinese are courteous! But there are others aren't so courteous. You know what I mean?"

I replied, again inches from the back of this guy's neck, "apparently, some people don't understand how to be wait in line."

Not exactly a "going postal" kind of outburst. No profanity. But because we were blond-haired blue-eyed American devils, and we were saying all this in Chinese, and loud, everyone was staring at us, and by extension, at Last Straw.

I'd like to tell you that he ran out of the building, and the onlookers applauded us.

So I will: He ran out of the building, and the onlookers applauded us.

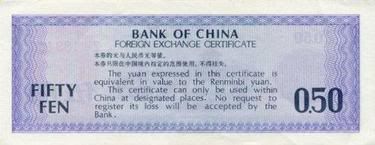

Only that didn't really happen. After awhile, Last Straw did find some excuse to move away from us – he probably found a better place to cut in line. After that, no more people cut in front of us. We got our return tickets to Beijing and got out of there. (This time we would be going hard sleeper instead of soft sleeper. And again we had succeeded in paying in RMB. Score! Another $7 saved.)

Our next order of business was to get bus tickets to our next destination, the town of Leshan, a few hours to the south of Chengdu. On the bus ride down People's Avenue, we passed by one of Chengdu's biggest attractions, the statue of Chairman Mao.

Chairman Mao, after all, had inspired the phrase "cult of personality." At one time there were thousands, probably tens of thousands of Chairman Mao statues all over China. But under Deng Xiaoping in the 80s, as China modernized and reformed, this type of leader worship was deemphasized. Deng did not allow any statues of himself to be erected, and Mao statues around the country came down in droves. In fact, the last statue of Mao at Bei Da* had been pulled down shortly after I arrived. Not many statues remained. (Sidenote: I always wanted to acquire one of these. I wanted to have a Chairman Mao head, maybe 5, 6 feet tall, in my back yard.)

I was fascinated by the Cultaral Revolution, and by the cult-like adoration for "the Great Helmsman." Though it was disappearing quickly, there was still quite a bit of evidence of how things must have been in the 1960s. There were the Mao badges that everyone had worn, now being sold to people like me. There were large slogans painted on walls. I remember walking onto the running track at Bei Da and being taken aback when I saw a political slogan on the wall, in characters that were probably 6 feet tall. Fading, but still there.

Bob and I found the bus station, and fortunately, buying bus tickets was much easier than buying train tickets. I guess not many people were planning to spend the first day of the new year taking a four-hour bus ride.

So there it was. We'd spent our first half-day in Chengdu doing nothing but organizing our escape. This was the rhythm of traveling in China, especially outside the major cities, that I became accustomed to. As soon as you arrive, figure out how and when you're going to leave.

Bob and I visited the Wenshu Monastery, which was literally across the street from our guesthouse. It was a real functioning Tibetan Buddhist monastery, with novice monks in saffron and brown robes circulating through the grounds.

We were there at an interesting time. It was New Year's, so many people were visiting to make offerings – to light incense and bow before the various altars. Furthermore, we learned that the 10th Panchen Lama had just passed away.

The Panchen Lama was the second highest ranking lama, behind the Dalai Lama. China had "liberated" Tibet in the early 1950s. In 1959, Tibetans staged an unsuccessful rebellion, during which the current Dalai Lama fled into exile in India. The Panchen Lama remained in China as the highest ranking lama in China.

The Panchen Lama had been a somewhat controversial figure. Was the Panchen Lama upholding and representing the Tibetan people, the spiritual leader who stayed to fight for his people? Or had he been co-opted by the hated Chinese occupiers? He had been jailed by the Chinese government. But he also married a Chinese woman and had a daughter. Before he died, he had made a speech highly critical of the Chinese occupation of Tibet.

The monastery was crowded with worshippers paying their respects. There was an altar adorned with a large portrait of the Panchen Lama, flanked by pyramids of oranges. People crowded around the altar to light incense.

I definitely had the sense that we were seeing something unusual and significant.

***

The next day, we visited another temple, on the outskirts of the city, called Baoguangsi. I don't remember too much about the temple - it had the usual assortment of ghoulish looking deities, which I've never enjoyed all that much. Mainly I remember that there was a somewhat prominent calligrapher there, and Bob and I talked to him. Bob found some connection with him, because Bob had attended UCLA, and the calligrapher's daughter was there. Something like that. He ended up making a poster for each of us. My poster, which said something about US-China friendship, is now hanging in a bathroom at my parents' house.

We also went to an open air market to replenish our snack supplies for our bus ride the next day. Since China didn't have a national highway system to speak of, the goods for sale in a market in Chengdu were really quite different than those in Beijing. Everything was a little different – clothes, books, and especially food. Imagine going to a grocery store in Cleveland, and almost none of the same goods are on the shelves that you're used to seeing at home. I was especially struck by how the market in Chengdu had different vegetables than what we saw in Beijing. Well, not only that, but I saw vegetables I'd never seen before. There were bright red radishes that looked like giant radioactive carrots. I wondered if there were giant rabbits with x-ray vision in the Sichuan countryside.

***

That night was Chinese New Year's Eve. The fireworks were getting louder and more frequent. In the evening, I took a shower. A "shower," you may recall, consisted of heating kettles of water on gas burners and pouring them over yourself as you stood in a tiled basin.

I heated my water, then stood in the basin. I mixed the hot water from the kettles in with some cold water. I poured it over myself. This was the first real shower I'd had since Beijing. It felt wonderful to be warm and clean. Wonderful, but then I realized it was still about 40 degrees in there, and I was freezing. I had to hurry up and do it again. I poured out my kettle, and poured it over myself, but I didn't get completely rinsed off, and now I was out of hot water. I needed to heat more water.

Wet, shivering, I set about quickly refilling the kettles. With shaky, wet hands, I tried to relight the gas burners. For a moment, it didn't light.

Just at that moment, a GIANT firecracker went off outside the window. For a split second I thought: great, I just blew myself up. What a way to go, too. They'll find me, sprawled naked in this tiled basin, covered in third-degree burns and goosebumps.

***

Chinese New Year's Eve was a little like Christmas Eve – what if there weren't any open restuarants? But then we reasoned: even though it's a holiday, some restaurant will be open. And odds are, it will be a Chinese restaurant.

We ended up sampling one of the local delicacies, Sichuan hotpot. It's kind of like a big pot of boiling oily soup, into which you add meat and vegetables, sort of like fondue. And also? It's very very spicy. The hallmark of Sichuan cooking is that not only is it spicy, but it also has a special peppery spice that makes your tongue tingly and numb. Regular spicy is "la." Sichuan spicy is "

ma la." It's delicious, and it's rarely replicated in Chinese food in the US. (It also made for fun jokes with servers. You could ask someone, are you afraid to eat tingly-spicy food? That would be: "Ni pa ma la ma?" Or: "Ni pa bu pa ma la?" Isn't that fun? Anyone else? Just me? Okay.)

We watched the CCTV New Year's program as we ate. We drank terrible local beer out of the plastic bowls provided by the restaurant. The servers invited us to go into the kitchen to select what we wanted to add to our hot pot. We chose a lot of vegetables, and some pork. We politely declined to have one of the sheep's brains that was neatly lined up on a tray.

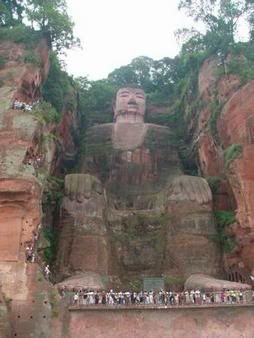

The next day, Bob and I boarded a bus for a four-hour ride to see the largest sitting Buddha statue in the world.

*In case you missed it: Bei Da = Beijing Daxue = Peking University.